Stock Based Compensation Cash Flow Statement Accounting Guide

Stock-based compensation can be a complex and nuanced topic when it comes to accounting for it on a cash flow statement. The accounting treatment for stock-based compensation is governed by ASC 718, which requires companies to expense the fair value of stock-based compensation over the vesting period.

Stock-based compensation is typically recorded as a non-cash expense on the income statement, but it also affects the cash flow statement. The cash outflow for stock-based compensation is reported as a financing activity on the cash flow statement.

Companies can use various methods to determine the fair value of stock-based compensation, including the Black-Scholes model. The Black-Scholes model is a widely used option pricing model that takes into account factors such as the stock price, exercise price, time to expiration, and volatility.

The accounting for stock-based compensation can have a significant impact on a company’s cash flow statement, particularly if the company has a large number of employees participating in the stock-based compensation plan.

For another approach, see: Project Finance Model

What Is

Credit: youtube.com, How Stock-based Compensation can DESTROY Value For Shareholders?

Stock Based Compensation (SBC) is recognized as a non-cash expense on the income statement under U.S. GAAP.

SBC is recorded as an operating cost, like wages, and is allocated to the relevant operating line items.

SBC issued to direct labor is allocated to cost of goods sold (COGS).

SBC to R&D engineers is included within R&D expenses.

SBC for management and those involved in selling and marketing is included in SG&A and other operating expenses.

The consolidated income statement will often not explicitly identify SBC on the income statement, but it’s there, inside the expense categories.

A business’s executives, directors, and employees are paid with the company’s stock via stock-based compensation, share-based compensation, or equity compensation.

Employee stock awards often have a vesting time before they become earned and marketable.

Here’s a breakdown of how SBC is allocated to different expense categories:

- Direct labor: Cost of Goods Sold (COGS)

- R&D engineers: R&D expenses

- Management and selling/marketing: SG&A and other operating expenses

Types of Stock-Based Compensation

Stock-based compensation comes in many forms, and understanding the different types can help you navigate the complex world of equity compensation. Non-qualified stock options (NSOs) and incentive stock options (ISOs) are two types of stock compensation, with ISOs only available to employees and offering special tax advantages.

Credit: youtube.com, Stock-Based Compensation – Accounting for Financial Modeling

There are also different types of share-based compensation, including restricted stock, stock options, stock appreciation rights (SARs), restricted stock units (RSUs), and performance shares. These types of compensation can be paid in cash or stock.

Employee stock purchase plans (ESPPs) let employees buy company shares at a discount, while phantom stock pays a cash bonus at a later date equaling the value of a set number of shares. These plans can be a great way for employees to benefit from their company’s growth.

Here are some common types of stock-based compensation:

- Restricted Stock: These are common shares with selling restrictions, typically coming with voting rights and dividends.

- Stock Options: These are non-tradeable call options on the employer’s stock, issued at the market price on the grant date.

- Stock Appreciation Rights (SARs): SARs give employees the right to the increase in the value of a designated number of shares, which can be paid in cash or stock.

- Restricted Stock Units (RSUs): RSUs represent a promise to employees to grant them shares or cash at a future date, without directly tying to the price of company shares.

- Performance Shares: These are awarded to employees based on the achievement of certain performance measures, such as earnings per share or return on equity.

In addition to these types, other forms of stock-based compensation include employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs) and shares, which represent fractional ownership interests in a company. Phantom shares also provide senior management and other chosen workers with the advantages of stock ownership without transferring any firm shares to them.

Grant and Vesting Process

The grant and vesting process for stock-based compensation is a crucial aspect of accounting for these transactions. It’s a promise of future value, not a current expense.

Credit: youtube.com, Stock-Based Compensation in a DCF

At the initial grant date, no journal entry is made for restricted stock units (RSUs) or stock options. It’s just a promise for now, with the company noting the fair value of the shares in their footnotes.

The vesting period is when the employee starts earning the shares or options. This is when the company records the cost of giving those shares to the employee.

Here’s a breakdown of the journal entries for the vesting period:

- Debit: SB Compensation Expense (for the value of the vested shares)

- Credit: Additional Paid-In Capital (APIC) (for the value of the vested shares)

For example, if an employee earns 500 shares with a value of $15 each, the company would record a debit of $7,500 (SB Compensation Expense) and a credit of $7,500 (APIC).

The company will make similar journal entries for the next two years, until all 1,500 shares are vested. This way, they’re spreading out the cost over the time the employee is earning those shares.

The key differences between restricted stock and stock options lie in how and when you get the shares. With restricted stock, you get the shares once they vest. With stock options, you need to take an extra step and decide if and when to buy those shares.

Recording and Valuation

Credit: youtube.com, Terry Smith – Stock-based compensation (2023)

Restricted stock and restricted stock units (RSUs) are typically valued at the market price of the underlying shares at the grant date.

The fair value of options is estimated using recognized financial models, such as the Black-Scholes model or binomial lattices, which incorporate variables like volatility, risk-free rates, and dividend yields.

For restricted stock, the valuation is straightforward, with the value recognized for each restricted share equal to its current share price. However, for restricted shares, the fair value is expected to be lower due to contractual or statutory limitations, although the impact on price is minimal in a crowded market.

Here’s a summary of the key valuation principles for stock-based compensation:

- Determine the fair value – Even if the equity may not be awarded until much afterwards, accounting for stock-based compensation is assessed at the fair value of the given securities as of the grant date.

- Fair value of non-vested shares – A nonvested share’s fair value is determined by treating it as if it had vested on the grant date.

- Fair value of restricted shares – The fair value of a restricted share is expected to be lower than the fair value of an unrestricted share due to contractual or statutory limitations.

Journal Entries

The accounting for restricted stock and stock options involves journal entries that reflect the costs and values associated with these types of compensation.

For restricted stock, the initial journal entry when the company grants the stock is a simple one, with no immediate impact on the income statement.

Credit: youtube.com, DEPRECIATION BASICS! With Journal Entries

The journal entry for restricted stock grants is: Debit – Contra-equity — Unearned (deferred) Compensation, Credit – Common Stock & APIC — Common Stock.

The value of the restricted stock is calculated as the number of shares granted multiplied by the current share price.

Here’s a breakdown of the journal entry:

The unearned compensation account is a contra-equity account that offsets the common stock and APIC account, making the balance sheet balance.

The income statement impact of restricted stock is recognized only when the shares vest, and the company records the stock-based compensation expense and credits the APIC account.

The journal entry for vesting period accounting is: Debit – SB Compensation Expense, Credit – APIC.

The company will make similar journal entries for the next two years, until all 1,500 shares are vested.

The key difference between restricted stock and stock options lies in the journal entries, particularly when the employee exercises the options.

For stock options, the journal entry when the employee exercises the options includes debiting cash received from the employee and crediting APIC – Stock Options.

Here’s an example of the journal entry:

The APIC – Stock Options account is adjusted to show that the options are now real shares.

Valuation Principles

Credit: youtube.com, Valuation Principle (3.2.1)

Valuation Principles are crucial in accounting for stock-based compensation. The fair value of stock-based compensation is determined at the grant date, even if the equity is not awarded until later.

To determine the fair value of stock-based compensation, a valuation approach like an option-pricing model is used. This approach takes into account variables like volatility, risk-free rates, and dividend yields.

The fair value of non-vested shares is determined by treating them as if they had vested on the grant date. This means that the value of non-vested shares is the same as the value of vested shares.

Restricted shares, on the other hand, have a lower fair value due to contractual or statutory limitations on their trade. However, these limitations have a minimal impact on the price at which the shares might be exchanged if the issuer’s shares are traded in a crowded market.

Here are some key valuation principles to keep in mind:

- Determine the fair value of stock-based compensation at the grant date.

- Treat non-vested shares as if they had vested on the grant date to determine their fair value.

- Restricted shares have a lower fair value due to contractual or statutory limitations.

- Use a valuation approach like an option-pricing model to determine the fair value of stock-based compensation.

These principles are essential in accurately valuing stock-based compensation and ensuring that financial statements are clear, accurate, and trustworthy.

Financial Statement Effects

Credit: youtube.com, An Introduction to Financial Accounting – 9.5.2- Stock-based Compensation Disclosure Example

The income statement is where stock-based compensation (SBC) has the most significant impact. SBC is recognized as a compensation expense, which reduces net income and affects the company’s profitability.

This expense is spread out over the vesting period of the award, as seen in Example 2. For instance, if a company granted an employee stock options with a fair value of $100,000 that vests over five years, the company would recognize a $20,000 expense annually for five years.

The income statement shows the direct impact of SBC on the company’s net income. In Example 4, it’s explained that SBC affects the company’s profitability, even though it doesn’t involve spending actual cash right away.

SBC also affects the balance sheet, but in a different way. The Additional Paid-In Capital (APIC) account is increased when SBC is recorded, as seen in Example 10. This represents the value added to the company by issuing these shares.

Credit: youtube.com, How Atlassian Uses Stock Based Compensation to Drive Free Cash Flow

Here’s a breakdown of how SBC affects the financial statements:

Note that SBC can also affect the cash flow statement, particularly through changes in APIC and other equity accounts. This is an important consideration when analyzing a company’s cash flows and financial performance.

Cash Flow and Disclosure

Companies don’t need to pay cash upfront when granting or vesting equity-settled awards like stock options or restricted stock.

The cash received from employees when they exercise stock options is recorded as a financing activity, equal to the strike price times the number of options exercised.

For cash-settled awards, the cash paid to settle the award is recorded in operating activities.

Companies must disclose details of share-based arrangements under IFRS 2, which often appear in financial statement notes and governance reports.

Cash Flows

Cash flows from stock-based compensation can be a bit tricky to understand, but it’s actually quite straightforward.

For equity-settled awards like stock options and restricted stock, there’s no immediate cash impact when the award is granted or vests.

Credit: youtube.com, The CASH FLOW STATEMENT for BEGINNERS

However, when an employee exercises a stock option, the cash received from the employee is recorded as a financing activity.

This means the company gets cash, but it’s not considered part of the company’s operating activities.

Cash-settled awards, on the other hand, require the company to pay cash to settle the award, which is recorded in operating activities.

Small businesses or startups can benefit from stock-based compensation because it allows them to reward employees without paying a lot of cash upfront.

This can be especially helpful for companies that don’t have a lot of cash on hand.

In fact, stock-based compensation can even help companies save cash while still rewarding their employees.

The initial recording of stock-based compensation is a non-cash expense, which means it doesn’t involve actual money leaving the company.

However, when employees exercise their options, the company receives cash, which is then added to the company’s accounts and reflected in the cash flow statement.

This can eventually influence the company’s cash flow, which is why it’s essential to understand the impact of stock-based compensation on a company’s overall financial health.

Disclosures

Credit: youtube.com, financial disclosures

Disclosures are a crucial aspect of financial reporting, and they’re not just about sharing information with investors. Under IFRS 2, companies must disclose details of share-based arrangements.

These disclosures often appear in financial statement notes and governance reports, providing a clear picture of a company’s compensation practices.

Compliance and Best Practices

Accurate accounting for Stock-Based Compensation (SBC) is crucial for ensuring compliance with specific rules set by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB).

FASB requires companies to be transparent and consistent in their financial reporting, which means properly valuing stock options using models like the Black-Scholes model.

Proper valuation is essential to avoid trouble with FASB, tax authorities, and auditors.

Companies need to use the right methods to calculate the value of stock options, which helps maintain trust with stakeholders and keeps the company safe from penalties.

Ignoring compliance can lead to inaccurate financial statements, which can have serious consequences.

Stock Options Key Differences

The key differences between restricted stock and stock options are more nuanced than you might think. One major distinction is that restricted stock is a grant of company stock that vests over time, whereas stock options give the holder the right to buy company stock at a predetermined price.

Credit: youtube.com, Employee Stock Options Explained | The Terms You Need To Know!

Restricted stock is typically granted with a vesting schedule, which means the employee doesn’t own the stock outright until the vesting period is complete. For example, a company might grant 1,000 shares of restricted stock with a 4-year vesting schedule. After 1 year, the employee owns 25% of those shares, and so on.

Stock options, on the other hand, give the holder the right to buy company stock at a predetermined price, known as the strike price. This means the holder can choose to exercise the option and buy the stock at the strike price, or let it expire worthless.

The strike price of a stock option is set by the company and is usually based on the market value of the stock at the time of grant. This means the holder may be able to buy the stock at a price lower than its current market value, which can be a great benefit.

Ensuring Compliance

Credit: youtube.com, What is Compliance and Why Is It Important?

Accurate accounting for stock-based compensation (SBC) is crucial for ensuring compliance with regulatory requirements. FASB sets specific rules for companies to follow when issuing SBC, and these rules are designed to ensure transparency and consistency in financial reporting.

Proper valuation of stock options is a key aspect of compliance. The Black-Scholes model is a popular method for calculating the value of stock options, but it requires careful application to ensure accuracy.

Companies must properly value their stock options using specific models like the Black-Scholes model to ensure compliance with FASB requirements. This valuation needs to be correct to avoid trouble with FASB, tax authorities, and auditors.

Ignoring FASB’s rules on SBC can lead to penalties and damage to a company’s reputation. By following the rules, companies can maintain trust with stakeholders and avoid potential issues.

Here are some key takeaways for ensuring compliance with FASB’s SBC rules:

- Properly value stock options using models like the Black-Scholes model

- Reverse expenses for unvested stock when employees leave early

- Accurately account for SBC expenses on financial statements

- Exclude SBC from net income when comparing companies with similar compensation patterns

Example and Case Studies

Let’s dive into some example and case studies to illustrate the concept of stock-based compensation and its impact on cash flow statements.

Credit: youtube.com, 64-Stock based Compensation Disclosure Example

In the case of Jones Motors, we saw how restricted stock was granted to employees with a service period of 3 years and vesting occurring only if employees stayed with the company for 2 years. The journal entries for restricted stock were straightforward, with debits to contra-equity and credits to common stock and APIC.

The key takeaway from the Jones Motors example is that the value recognized for each restricted share is the same as its current share price. This is a crucial point to remember when analyzing companies with significant stock-based compensation.

For instance, DEF Company granted 1,000 restricted stock units (RSUs) to an employee, with a fair value of $20 per share. The shares will vest evenly over four years, with 25% vesting each year. The journal entries for DEF Company are similar to those of Jones Motors, with debits to SB Compensation Expense and credits to Additional Paid-In Capital (APIC).

GHI Company, on the other hand, granted 2,000 stock options to an engineer, with an exercise price of $15 per share and a fair value of $7 per option. The options will vest over four years, with 25% vesting each year. The journal entries for GHI Company are also similar, with debits to SB Compensation Expense and credits to APIC – Stock Options.

Interpreting the Statement of Cash Flows: Operating, Investing, and Financing

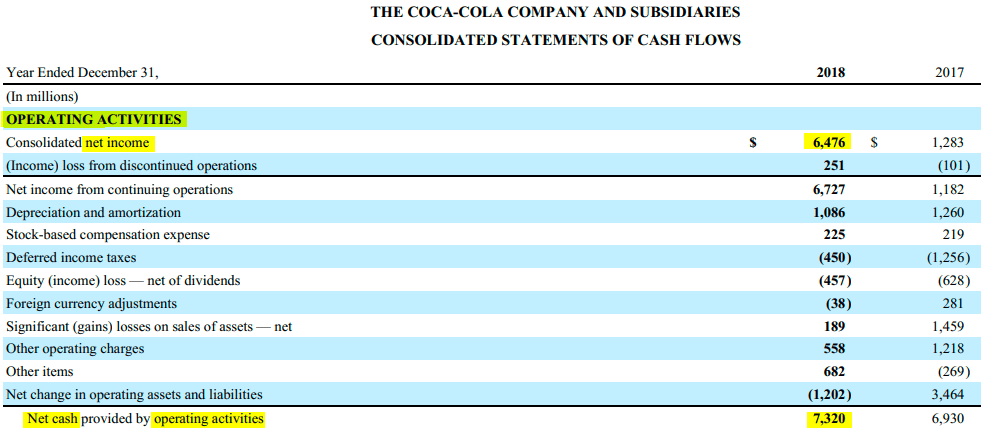

A lot of critical information can be learned from the statement of cash flows. As cash flows to shareholders are what investing is all about, being able to understand all the great information provided by the cash flow statement is very valuable stuff to investors. When doing a valuation, investors will be able to adjust their analysis for non-cash or growth items, as well as spot problems in the business’s sustainability.

This article will discuss some of the most important items in the cash flow statement using Coca-Cola as an example for some important items.

The Direct vs. Indirect Method – A Quick Note

There are technically two methods to produce a statement of cash flows; the direct method and the indirect method. However, it is the norm for major companies, such as Coca-Cola to report under the indirect method. The direct method is, as it sounds, a recreation of the income statement based on cash flows rather than accrual accounting standards. The indirect method can more accurately be described as a reconciliation of net income to cash flows, with all the reconciling items listed out in separate categories which are cash flows from operations, cash flows from investing activities, and cash flows from financing activities.

Cash Flows from Operations (CFO)

As the lifeblood of the business, positive cash flows from operations (CFO) prove that the business can sustain general operations before making any long-term investments (to be discussed next). Under the indirect method, the statement of cash flows starts at net income and then adjust for the items where cash hasn’t changed hands. As will be seen, not all income under accrual accounting necessarily makes it into CFO. Current assets and liabilities on the balance sheet will eventually flow through CFO when the actual cash changes hands, which is not always the same as accrual accounting based income.

Working Capital – Working capital is an all-encompassing term for items such as accounts receivable, accounts payable, and inventory. Working capital by itself can be judged as a cash conversion cycles and also by analyzing trends over time to see how good sales terms the company is giving to customers as well as what they are getting from suppliers. Growth in a business requires more working capital to support the sales and, as such, always eats up a little cash flow.

Depreciation – In non-accrual accounting terms, depreciation is a non-cash expense that is the historical cost of fixed assets previously purchased coming off the balance sheet as an expense through net income. Later within investing cash flows on the statement, they will subtract out the actual cash capital expenditures in the period.

Stock Based Compensation – This cash flow item is always interesting as it gives some perspective on the appropriateness of stock based compensation at the company. The stock based compensation expense needs to be added back as it is accrued for along with accounting standards, but no cash is necessarily leaving the company but shareholders are just being diluted by the approximate worth.

Equity Income net of Dividends – Using Coke as an example, their income from equity accounted investments would relate to investments in businesses such as bottlers within the Coke network. The proportional net income owned of this equity investment is included in net income but cash (ie. dividends) are not necessarily received and as such, this non-dividend portion of net income needs to be subtracted from CFO.

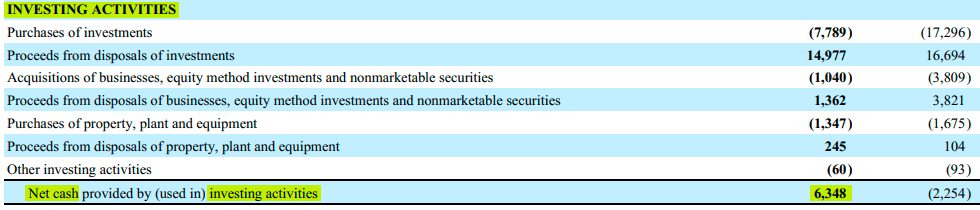

Cash Flows Provided By (Used In) Investing Activities

Long-term assets on the balance sheet are investments that flow through a separate part of the cash flow statement. These investments will have a payback period over many years so they are separated from operating cash flows which are more fluid in nature and linked to net income.

Capital Expenditures (CapEx) – These are the actual cash capital expenditures (CapEx) for fixed assets, or property, plant, and equipment (PP&E) in the period. These expenditures are being capitalized and will later be depreciated through net income. These capital investments can be either maintenance CapEx made to sustain the ongoing operations, or growth CapEx made to increase the value of the business. When growth CapEx is a major percentage of CapEx, investors could consider adjusting away some CapEx in a zero-growth valuation analysis. In Coke’s case, we can see that purchases of PP&E ($1,347M in 2018) are similar and not significantly greater than depreciation ($1,086M). This sort of general increase is expected and is due to inflation as the assets being depreciated are purchases made years ago at historical deflated prices.

Side Note on Free Cash Flows: The largely talked about Free Cash Flow (FCF) figure that is used in net present valuations methods can be quickly approximated by taking cash flow from operations (where non-cash depreciation has been added back) and subtracting CapEx. To get even more accurate, adjustments to changes in working capital and maintenance CapEx can be made.

Purchase of Investments – These are short-term investments which show as the “equivalents” in cash and equivalents on the balance sheet. Think about Coke investing its substantial cash on the balance sheet in short-term investments and money-market funds.

Acquisitions – When a company chooses to buy another business’s assets outright rather than slowly build the assets themselves through CapEx, this is separately disclosed on the statement of cash flows. Acquisitions can generally be regarded as growth CapEx but if acquisitions are regular and form part of the company’s business strategy, then the amount should at least partially be included in a net present valuation of cash flows.

Purchase of Goodwill & Intangibles: When an acquisition is made above book value, purchase of goodwill and intangibles that are not tangible PP&E will be broken out separately. In this way, the proportional cash outflows of the investment are being separated into the associated asset category that these items will be added to on the balance sheet.

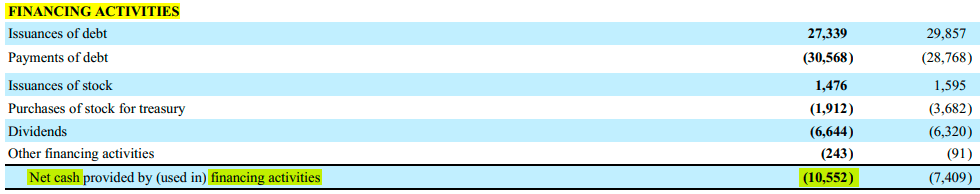

Financing Cash Flows

This is probably my favorite part of the cash flow statement because it shows what money is getting returned to shareholders. In addition to shareholder capital and equity, financing cash flows also include changes in the capital of the business due to debt issuance or repayment. Other more exotic capital raising instruments such as warrants would also be part of financing cash flows.

If a business is investing more cash into the business than it is generating from operations, these excess cash needs will have to be financed from outside investor capital. For each item within financing cash flows, one can think of it as whether the business is raising capital from investors, or my favorite, returning capital to investors.

Cash Dividends Paid –Just as it sounds, this is capital being returned to equity investors in the form of dividends. Notably, if the company has a dividend reinvestment program (DRIP), these stock dividends would not be included here in these cash distributions. It is important to always give a look to see if dividends, whether cash or DRIP, are truly being covered by free cash flows as discussed earlier.

Shares Repurchased (Issued) – The amount of money spent on share buybacks can be seen in this figure. The amount of share repurchases can be added to dividends to come up with total shareholder yield figures. In Coke’s case, they returned $6,644M to investors in dividends during 2018 and purchased stock (net of stock issuances) of $436M. This indicates total shareholder yields of $7,080M which can be divided into the current market capitalization of the company to give a total shareholder yield.

On the other hand, share issuances are often referred to as dilution to shareholders and could be subtracted from the dividends to obtain the true shareholder yield.

Debt Repayment (Issued) – Additional cash needs are often first financed by issuing debt until the growing debt load becomes unsustainable. If capital expenditures aren’t covered by CFO or if cash dividends aren’t being covered by FCF, a good place to look for where that extra cash might be coming from is debt issuance.

Being able to intepret the statement of cash flows is a key learning for every investor. For investors interested in a pre-built financial model where they can punch in the financial data of any company of interest, they can check out our financial model and valuation template!

https://www.cgaa.org/article/stock-based-compensation-cash-flow-staementehttps://einvestingforbeginners.com/interpreting-the-statement-of-cash-flows-csmith/