Capital Expenditure (CapEx)

Over 2 million + professionals use CFI to learn accounting, financial analysis, modeling and more. Unlock the essentials of corporate finance with our free resources and get an exclusive sneak peek at the first module of each course. Start Free

What is a Capital Expenditure (CapEx)?

A capital expenditure (“CapEx” for short) is the payment with either cash or credit to purchase long-term physical or fixed assets used in a business’s operations. The expenditures are capitalized (i.e., not expensed directly on a company’s income statement) on the balance sheet and are considered an investment by a company in expanding its business.

CapEx is important for companies to grow and maintain their business by investing in new property, plant, equipment (PP&E), products, and technology. Financial analysts and investors pay close attention to a company’s capital expenditures, as they do not initially appear on the income statement but can have a significant impact on cash flow.

Capital expenditures normally have a substantial effect on the short-term and long-term financial standing of an organization. Therefore, making wise capex decisions is of critical importance to the financial health of a company. Many companies usually try to maintain the levels of their historical capital expenditures to show investors that they are continuing to invest in the growth of the business.

Key Highlights

- A capital expenditure, or CapEx, is the purchase of long-term physical or fixed assets used in a business’s operations.

- Financial analysts and investors pay close attention to a company’s capital expenditures, as they do not initially appear on the income statement but can have a significant impact on cash flow.

- The calculation of free cash flow deducts capital expenditures. Free cash flow is one of the most important calculations in finance and serves as the basis for valuing a company.

When to Capitalize vs. Expense

The decision of whether to expense or capitalize an expenditure is based on how long the benefit of that spending is expected to last. If the benefit is less than 1 year, it must be expensed directly on the income statement. If the benefit is greater than 1 year, it must be capitalized as an asset on the balance sheet.

For example, the purchase of office supplies like printer ink and paper would not fall under investing activities on the cash flow statement but would instead be an operating expense on the income statement.

The purchase of a building, by contrast, would provide a benefit of more than 1 year and would thus be deemed a capital expenditure.

Learn more about when to capitalize on the IFRS website.

CapEx on the Cash Flow Statement

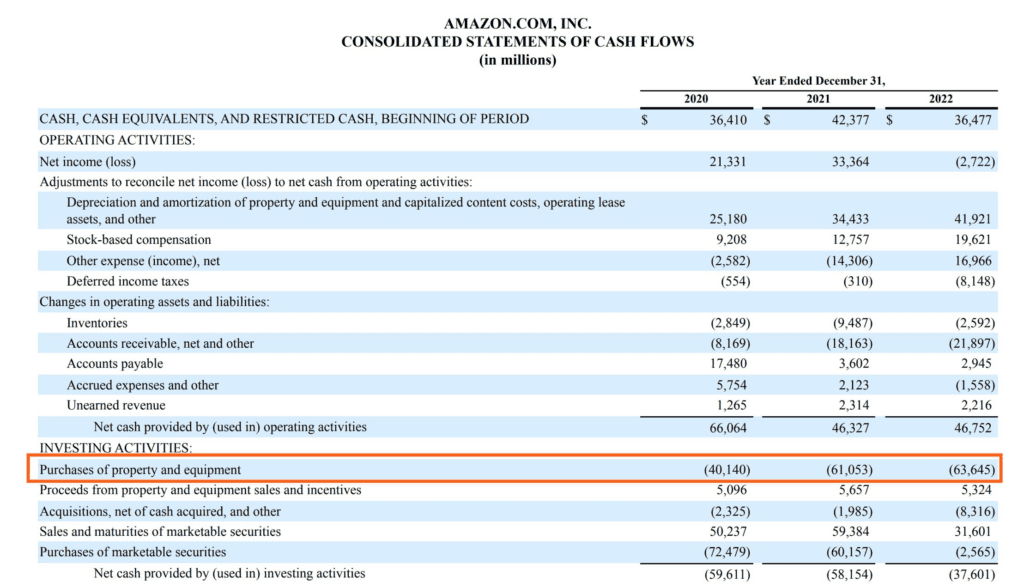

Capital expenditures can be found on a company’s cash flow statement under “investing activities.” As you can see in the screenshot above from Amazon’s 2022 annual report (10-k), in 2022, Amazon had $63,645 million of capital expenditure related to “purchases of property and equipment.”

Since this spending is considered an investment, it does not appear on the income statement.

CapEx on the Balance Sheet

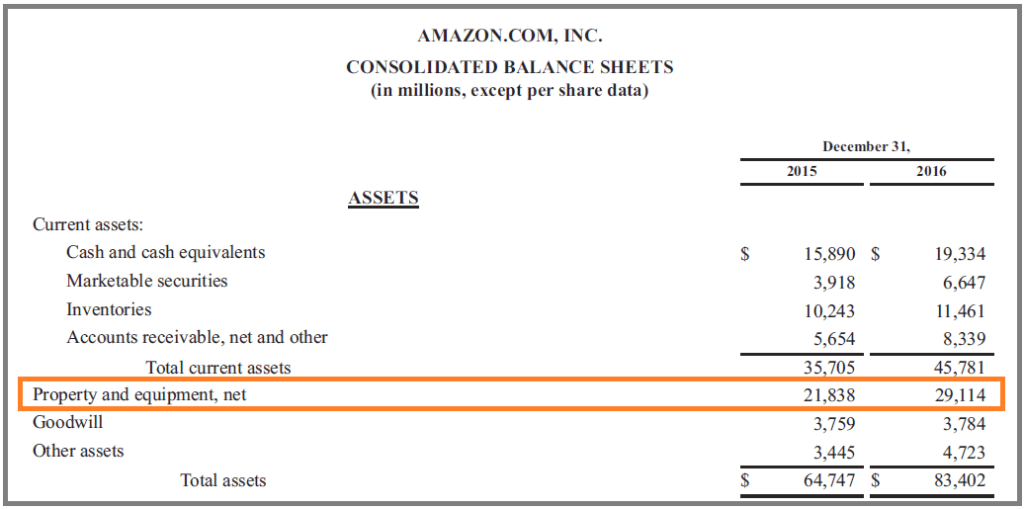

CapEx flows from the cash flow statement to the balance sheet. Once capitalized, the value of the asset is slowly reduced over time (i.e., expensed) via depreciation expense.

How to Calculate Net Capital Expenditure

Net CapEx can be calculated either directly or indirectly. In the direct approach, an analyst must add up all of the individual items that make up the total expenditures, using a schedule or accounting software. In the indirect approach, the value can be inferred by looking at the value of assets on the balance sheet in conjunction with depreciation expense.

Direct Method

- Amount spent on asset #1

- Plus: Amount spent on asset #2

- Plus: Amount spent on asset #3

- Less: Value received for assets that were sold

- = Net CapEx

Indirect Method

- PP&E Balance in the current period

- Less: PP&E balance in the previous period

- Plus: Depreciation in the current period

- = Net CapEx

Read more about the CapEx Formula.

Capital Expenditure and Depreciation

As a recap of the information outlined above, when an expenditure is capitalized, it is classified as an asset on the balance sheet. In order to move the asset off the balance sheet over time, it must be expensed and moved through the income statement.

Accountants expense assets onto the income statement via depreciation. There is a wide range of depreciation methods that can be used (straight line, declining balance, etc.) based on the preference of the management team.

Over the life of an asset, total depreciation will be equal to the net capital expenditure. If a company regularly has more CapEx than depreciation, its asset base is growing.

Here is a guideline to see if a company is growing or shrinking (over time):

Capital Expenditure in Free Cash Flow

Free Cash Flow is one of the most important metrics in corporate finance. Analysts regularly evaluate a company’s ability to generate cash flow and consider it one of the main ways a company can create shareholder value.

The formula for Free Cash Flow (FCF) is:

FCF = Cash from Operations – Capital Expenditures

CapEx in Valuation

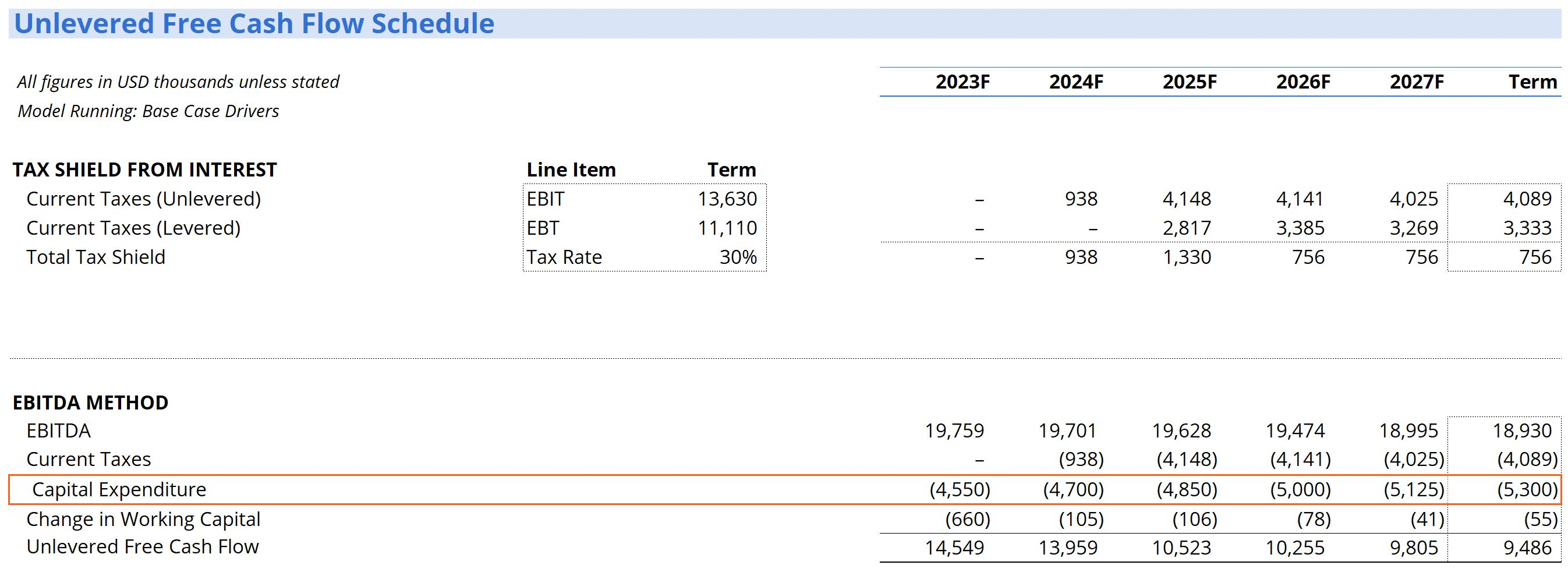

In financial modeling and valuation, an analyst will build a DCF model to determine the net present value (NPV) of the business. The most common approach is to calculate a company’s unlevered free cash flow (free cash flow to the firm) and discount it back to the present using the weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

Below is a screenshot of a financial model calculating unlevered free cash flow, which is impacted by capital expenditures.

Types of Capital Expenditures

There are normally two forms of capital expenditures:

- Maintenance capex: Expenditures to maintain current levels of a company’s operations

- Growth capex: Expenditures that will enable an increase in future growth

It is important to note that funds spent on repair or in conducting normal maintenance on assets are not considered capital expenditures and should be expensed on the income statement.

Importance of Capital Expenditures

Decisions on how much to invest in capital expenditures can often be extremely vital decisions made by an organization. They are important because of the following reasons:

1. Long-term Effects

The effect of capital expenditure decisions usually extends into the future. The range of current production or manufacturing activities is mainly a result of past capital expenditures. Similarly, the current decisions on capital expenditures will have a major influence on the future activities of the company.

Capital investment decisions are a driver of the direction of the organization. The long-term strategic goals, as well as the budgeting process of a company, need to be in place before authorization of capital expenditures.

2. Irreversibility

Capital expenditures are often difficult to reverse without the company incurring losses. Most forms of capital equipment are customized to meet specific company requirements and needs. The market for used capital equipment is generally very poor.

3. High Initial Costs

Capital expenditures are characteristically very expensive, especially for companies in industries such as manufacturing, telecom, utilities, and oil exploration. Capital investments in physical assets like buildings, equipment, or property offer the potential to provide benefits in the long run but will need a large monetary outlay initially.

4. Depreciation

Capital expenditures have an initial increase in the asset accounts of an organization. However, once capital assets start being put in service, depreciation begins, and the assets decrease in value throughout their useful lives.

Challenges with Capital Expenditures

Even though capital expenditure decisions are very critical, they create more complexity:

1. Measurement Problems

The accounting process of identifying, measuring, and estimating the costs relating to capital expenditures may be quite complicated.

2. Unpredictability

Organizations making large investments in capital assets hope to generate predictable outcomes. However, such outcomes are not guaranteed, and losses may be incurred. The costs and benefits of capital expenditure decisions are usually characterized by a lot of uncertainty. Even the best forecasters sometimes make mistakes. During financial planning, organizations need to account for risks to mitigate potential losses, even though it is not possible to eliminate them.

Efficient Capital Expenditure Budgeting Practices

Major capital projects involving huge amounts of capital expenditures can get out of control quite easily if mishandled and end up costing an organization a lot of money. However, with effective planning, the right tools, and good project management, that doesn’t have to be the case. Here are some of the secrets that will ensure the budgeting of capital expenditures is efficient.

1. Structure Before You Start

Capital expenditure budgets need adequate preparations before commencement. Otherwise, they might go over budget. Before starting a project, you need to find the scope of the project, work out realistic deadlines, and ensure that the whole plan is reviewed and approved.

It is at this stage that you should think about how many internal resources will be required by the project, including manpower, materials, finances, and services. To have a more accurate budget, you should have more detail going into the project.

2. Think Long Term

At the start of your capital expenditure project, you need to decide whether you will purchase the capital asset with debt or set aside existing funds for the purchase. Saving money for the purchase usually implies that you will have to wait for a while before getting the asset you need.

However, borrowing money leads to increased debt and may also create problems for your borrowing ability in the future. Both choices can be good for your company, and different choices might be needed for different projects.

3. Use Good Budgeting Software

From the beginning of the project, you should choose a reliable, practical program to manage the budgeting. The type of budgeting software you choose will depend on such things as the scale of the project, the speed of the program, and the risk of error.

4. Capture Accurate Data

Accurate data is very crucial if you want to manage capital projects efficiently. To create a realistic budget and generate valuable reports, you need to gather reliable information.

5. Levels of Detail Should Be Optimal

Trying to put in too much detail will result in too much time being spent in gathering information to make the budget, which may be outdated by the time the budget is finished. However, too little detail will make the budget vague and, therefore, less useful. The right optimal balance needs to be found.

6. Form Clear Policies

Since the management of capital expenditures in a large organization may involve numerous employees, departments, or even regions, clear policies for everyone to follow should be put in place to put the budget on track.

Additional Resources

Thank you for reading CFI’s guide to Capital Expenditures. To keep advancing your career, these additional CFI resources will be useful:

Get Certified for Financial Modeling (FMVA)®

Gain in-demand industry knowledge and hands-on practice that will help you stand out from the competition and become a world-class financial analyst.

Mastering Fixed Asset Depreciation for Financial Accuracy

Fixed asset depreciation is more than an accounting exercise—it’s a critical component of financial accuracy that impacts everything from tax liability to investor confidence. Mastering depreciation methods ensures your financial statements reflect the true economic reality of your business.

For organizations of all sizes, fixed assets represent significant capital investments that decline in value over time. Properly accounting for this decline through depreciation is essential for accurate financial reporting, tax compliance, and business decision-making.

According to a study by the American Institute of CPAs, depreciation-related errors account for approximately 14% of all financial statement restatements. These errors can lead to serious consequences, including tax penalties, reduced investor confidence, and flawed business decisions based on inaccurate financial data.

This article provides a comprehensive guide to mastering fixed asset depreciation, covering the various depreciation methods, best practices for financial accuracy, common pitfalls to avoid, regulatory compliance considerations, and practical examples to illustrate these concepts in action.

Whether you’re a financial professional seeking to refine your depreciation practices or a business leader looking to understand the impact of depreciation on your organization’s financial health, this guide will equip you with the knowledge and tools to ensure precision in your fixed asset accounting.

Depreciation Methods

Selecting the appropriate depreciation method is crucial for accurately reflecting how assets lose value over time. Each method allocates an asset’s cost differently across its useful life, and the best choice depends on the nature of the asset and how it’s used in your business.

Primary Depreciation Methods

Here are the most commonly used depreciation methods and their applications:

| Method | Description | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Straight-Line | Equal depreciation amount each year | Assets that depreciate steadily (buildings, furniture) |

| Declining Balance | Accelerated depreciation with higher amounts in early years | Technology and equipment that quickly becomes obsolete |

| Sum-of-Years-Digits | Accelerated method based on years of useful life remaining | Assets with higher productivity in early years |

| Units of Production | Based on actual usage or production | Manufacturing equipment, vehicles, natural resource assets |

| MACRS | Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (U.S. tax method) | Tax reporting for most U.S. businesses |

Depreciation Method Comparison

To illustrate how different depreciation methods affect financial statements, let’s compare them using a common example:

- Asset cost: $100,000

- Estimated useful life: 5 years

- Estimated salvage value: $10,000

Chart: Comparison of depreciation methods over a 5-year period

| Year | Straight-Line | Double Declining Balance | Sum-of-Years-Digits | Units of Production* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | $18,000 | $40,000 | $30,000 | $22,500 |

| Year 2 | $18,000 | $24,000 | $24,000 | $18,000 |

| Year 3 | $18,000 | $14,400 | $18,000 | $27,000 |

| Year 4 | $18,000 | $8,640 | $12,000 | $13,500 |

| Year 5 | $18,000 | $2,960 | $6,000 | $9,000 |

| Total | $90,000 | $90,000 | $90,000 | $90,000 |

*Units of Production example assumes varying usage levels across years

Method Selection Criteria

Consider these factors when selecting a depreciation method:

Asset Usage Pattern

Choose a method that best reflects how the asset’s value diminishes over time. Assets that lose value quickly in early years benefit from accelerated methods.

Financial Reporting Goals

Consider how depreciation affects financial ratios and metrics that stakeholders use to evaluate your business performance.

Tax Implications

Accelerated methods can provide larger tax deductions in early years, improving cash flow, but may require maintaining separate books for tax and financial reporting.

Industry Standards

Consider common practices in your industry to ensure comparability with peer companies and meet industry-specific regulatory requirements.

Advanced Depreciation Considerations

Component Depreciation

For complex assets with components that have different useful lives, component depreciation allows you to depreciate each significant part separately. This approach is particularly relevant for:

- Buildings (structure, HVAC systems, elevators, roof)

- Aircraft (airframe, engines, interiors)

- Manufacturing equipment with replaceable components

Revaluation Model

Under IFRS (but not US GAAP), companies can choose to use the revaluation model for certain asset classes, where assets are periodically revalued to fair market value. This approach:

- Provides more current asset values on the balance sheet

- Creates more complex accounting with revaluation surpluses/deficits

- Requires regular professional valuations

Depreciation Recapture

When assets are sold for more than their depreciated value but less than original cost, tax authorities may “recapture” some depreciation as ordinary income rather than capital gains. This has significant tax planning implications when disposing of depreciated assets.

Understanding the various depreciation methods and their implications is the foundation of accurate fixed asset accounting. The method you select should align with both the economic reality of how your assets lose value and your organization’s financial and tax objectives.

Best Practices for Financial Accuracy

Implementing robust practices for fixed asset depreciation goes beyond selecting the right method. These best practices ensure your depreciation calculations remain accurate, consistent, and compliant throughout the asset lifecycle.

Comprehensive Asset Records

Maintain detailed records for each asset that include:

- Acquisition Documentation – Purchase orders, invoices, contracts, and payment records

- Asset Details – Description, location, serial numbers, and responsible department

- Financial Information – Original cost, capitalization date, useful life estimate, and salvage value

- Depreciation Parameters – Method selected, depreciation schedule, and accumulated depreciation

- Maintenance History – Records of significant repairs, improvements, or modifications

Pro Tip: Asset Tagging

Implement a physical and digital asset tagging system that connects each physical asset to its corresponding record in your asset management system. This facilitates accurate tracking and periodic physical verification.

Regular Asset Reviews and Adjustments

Periodic Reassessment

Schedule regular reviews (at least annually) of key depreciation assumptions:

- Useful life estimates

- Salvage value projections

- Depreciation method appropriateness

- Asset condition and functionality

Impairment Testing

Conduct impairment assessments when indicators suggest an asset’s carrying value may exceed its recoverable amount:

- Significant market value declines

- Technological obsolescence

- Changes in legal or business environment

- Evidence of physical damage

Accounting for Changes in Estimates

When you revise useful life or salvage value estimates:

- Apply changes prospectively (to current and future periods)

- Recalculate depreciation based on the asset’s current carrying value

- Document the justification for the change

- Disclose significant changes in financial statement notes

Technology and Automation

Leverage technology to improve depreciation accuracy and efficiency:

| Technology Solution | Benefits | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Asset Management Software | Automated calculations, built-in compliance rules, audit trails | Integration with accounting systems, data migration, user training |

| Barcode/RFID Asset Tracking | Streamlined physical verification, location tracking, reduced errors | Hardware costs, tag durability, scanning infrastructure |

| Integrated ERP Systems | Unified data, automated journal entries, comprehensive reporting | Implementation complexity, customization requirements, cost |

| Data Analytics Tools | Pattern recognition, anomaly detection, predictive maintenance | Data quality requirements, analytical expertise, tool selection |

Documentation and Control Procedures

Establish clear policies and procedures for:

Asset capitalization thresholds and criteria

Depreciation method selection by asset class

Useful life determination guidelines

Salvage value estimation methodology

Periodic reconciliation between asset subledger and general ledger

Physical inventory verification procedures and frequency

Asset retirement and disposal approval process

Documentation requirements for each stage of the asset lifecycle

Cross-Functional Collaboration

Effective fixed asset management requires collaboration across multiple departments:

Finance/Accounting

- Depreciation calculation and recording

- Financial statement preparation

- Tax compliance and reporting

Operations/Facilities

- Asset utilization monitoring

- Maintenance scheduling

- Physical condition assessment

IT Department

- Asset management system support

- Technology asset lifecycle management

- Data security and backup

Procurement

- Asset acquisition documentation

- Vendor warranty management

- Replacement planning

Establish regular communication channels and shared responsibilities across these departments to ensure comprehensive asset management throughout the entire lifecycle.

Implementing these best practices creates a robust framework for depreciation management that enhances financial accuracy, strengthens internal controls, and provides reliable information for business decision-making. Regular reviews and continuous improvement of these practices will help your organization adapt to changing business needs and regulatory requirements.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Even well-intentioned organizations can make depreciation errors that compromise financial accuracy. Understanding these common pitfalls helps you implement preventive measures and detect issues before they impact your financial statements.

Inaccurate Asset Valuation

Incorrectly determining the depreciable base by:

- Omitting eligible capitalized costs (shipping, installation, etc.)

- Including ineligible costs (routine maintenance, repairs)

- Failing to separate land (non-depreciable) from buildings

- Not adjusting for trade-in allowances or incentives

Useful Life Misjudgments

Errors in estimating how long assets will provide value:

- Using standardized lives without considering specific usage

- Failing to adjust for technological obsolescence

- Not differentiating between physical life and economic utility

- Ignoring industry experience and historical data

Inconsistent Application

Failing to maintain consistency in depreciation practices:

- Using different methods for similar assets without justification

- Changing methods without proper documentation

- Inconsistent treatment of improvements vs. repairs

- Varying capitalization thresholds across departments

Ghost Assets

Continuing to depreciate assets that are no longer in service:

- Missing or delayed disposal documentation

- Inadequate physical verification procedures

- Poor communication between departments

- Failure to update records after asset transfers

Calculation and System Errors

Technical mistakes that compromise depreciation accuracy:

Common Calculation Errors

- Incorrect depreciation start dates (full month vs. pro-rated)

- Formula errors in spreadsheet-based calculations

- Failure to adjust for partial year depreciation

- Miscalculation of accelerated depreciation rates

- Continuing depreciation beyond an asset’s net book value

System Implementation Issues

- Improper system configuration or parameter settings

- Data migration errors when implementing new systems

- Inadequate testing of calculation algorithms

- Failure to reconcile system outputs with expected results

- Insufficient user training on system functionality

Preventive Controls and Detection Measures

Implement these safeguards to prevent and detect depreciation errors:

Preventive Controls

- Detailed written policies and procedures

- Required approvals for key depreciation decisions

- System validation rules and edit checks

- Standardized templates for calculations

- Proper segregation of duties

Detection Measures

- Regular reconciliations and analytical reviews

- Exception reporting for unusual patterns

- Periodic physical inventory verification

- Independent review of depreciation calculations

- Internal audit testing of asset controls

Real-World Error Case Studies

Case Study 1: Manufacturing Company Restatement

A mid-sized manufacturing company had to restate three years of financial statements after discovering they had been double-counting depreciation on equipment transferred between facilities. The error occurred because:

- Assets were not properly retired from the original location’s books

- New asset records were created at the receiving location

- No reconciliation process existed to identify duplicate assets

The restatement reduced reported expenses by $2.3 million and increased net income across the affected periods.

Case Study 2: Retail Chain Impairment Failure

A retail chain failed to recognize impairment on store fixtures and improvements for underperforming locations, continuing to depreciate these assets at original values despite clear indicators of impairment:

- Several stores had negative cash flows for multiple consecutive quarters

- No formal impairment testing process was in place

- Management focused on expansion rather than performance of existing locations

When eventually recognized, the impairment charge of $12 million significantly impacted a single quarter’s results, triggering a shareholder lawsuit alleging delayed recognition of the impairment.

Awareness of these common pitfalls allows you to implement targeted controls and review procedures that safeguard financial accuracy. Regular training for accounting staff on depreciation concepts and procedures is also essential for minimizing errors and ensuring consistent application of your organization’s policies.

Regulatory Compliance

Depreciation practices are subject to various accounting standards, tax regulations, and industry-specific requirements. Maintaining compliance with these frameworks is essential for accurate financial reporting and avoiding penalties or restatements.

Key Regulatory Frameworks

| Framework | Scope | Key Depreciation Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| US GAAP (ASC 360) | Financial reporting for US companies | Cost allocation over useful life, impairment testing, component approach optional |

| IFRS (IAS 16) | Financial reporting for companies following international standards | Component approach required, revaluation model permitted, annual review of estimates |

| US Tax Code (MACRS) | Tax reporting for US businesses | Prescribed recovery periods by asset class, accelerated methods, half-year/mid-quarter conventions |

| SEC Regulations | Public companies in the US | Enhanced disclosure requirements, materiality considerations, internal control certification |

| Industry-Specific Regulations | Varies by industry (utilities, banking, etc.) | Special depreciation rules, regulatory reporting requirements, industry-specific asset classes |

Book vs. Tax Depreciation

Understanding the differences between financial reporting (book) and tax depreciation is crucial for compliance:

| Aspect | Book Depreciation | Tax Depreciation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Reflect economic reality of asset usage | Maximize tax deductions within legal framework |

| Method Selection | Management judgment based on usage pattern | Prescribed by tax code (MACRS in the US) |

| Useful Life | Based on expected economic utility | Based on statutory recovery periods |

| Salvage Value | Considered in calculations | Generally not considered (assumed zero) |

| Mid-year Conventions | Various approaches based on policy | Specific conventions required (half-year, mid-quarter, etc.) |

Compliance Best Practices

Stay Current with Regulations

- Subscribe to regulatory updates from accounting bodies

- Participate in industry groups and forums

- Engage with tax advisors and auditors regularly

- Implement a formal regulatory change management process

Maintain Robust Documentation

- Document depreciation policy decisions and rationales

- Keep records of method selections and useful life determinations

- Maintain support for significant estimates and judgments

- Archive historical depreciation schedules and calculations

Reconcile Book and Tax Differences

- Maintain separate depreciation schedules for book and tax

- Track temporary differences for deferred tax calculations

- Reconcile differences as part of period-end close

- Document tax positions for uncertain areas

Implement Review Procedures

- Establish multi-level review of depreciation calculations

- Perform analytical reviews to identify unusual patterns

- Conduct periodic compliance self-assessments

- Engage external experts for complex or material issues

Special Regulatory Considerations

Bonus Depreciation and Section 179

US tax provisions that allow for accelerated deductions:

- Bonus depreciation permits immediate expensing of a percentage of qualified asset costs

- Section 179 allows businesses to deduct the full purchase price of qualifying equipment

- These provisions have specific eligibility requirements and dollar limitations

- Phase-out schedules and percentages change frequently with tax legislation

Leased Asset Considerations

Recent changes to lease accounting standards (ASC 842/IFRS 16) have significant depreciation implications:

- Right-of-use assets for operating leases now appear on balance sheets

- These assets must be depreciated over the lease term or useful life

- Lease term determination affects depreciation calculations

- Lease modifications require reassessment of depreciation schedules

Industry-Specific Regulations

Examples of specialized depreciation requirements by industry:

- Utilities: Regulatory accounting may differ from GAAP for rate-setting purposes

- Banking: Special considerations for foreclosed assets and loan collateral

- Healthcare: Unique requirements for medical equipment and facilities

- Natural Resources: Depletion accounting for mineral rights and reserves

Disclosure Requirements

Ensure your financial statement disclosures include these required elements:

- Depreciation methods used for each major asset class

- Useful lives or depreciation rates applied

- Total depreciation expense for the period

- Gross carrying amounts and accumulated depreciation by asset class

- Impairment losses recognized during the period

- Significant changes in estimates affecting depreciation

- Assets pledged as security for liabilities

- Contractual commitments for asset acquisitions

Navigating the complex regulatory landscape for depreciation requires ongoing attention to changing requirements and careful documentation of compliance efforts. By implementing robust processes to address these requirements, you’ll minimize compliance risks and ensure your financial reporting accurately reflects your organization’s fixed asset economics.

Practical Examples

To illustrate the concepts discussed throughout this article, let’s examine practical examples of depreciation in different scenarios. These examples demonstrate how depreciation methods, best practices, and compliance considerations apply in real-world situations.

Example 1: Manufacturing Equipment

A manufacturing company purchases a new production line for $750,000. The equipment is expected to have a useful life of 8 years and a salvage value of $50,000. The company expects the equipment to produce 4,000,000 units over its lifetime, with higher production in early years.

- Production pattern suggests accelerated depreciation

- Equipment has identifiable components with different lifespans

- Tax incentives available for manufacturing equipment

- Regular maintenance will affect useful life

- Use double-declining balance for financial reporting

- Apply component accounting for major replaceable parts

- Utilize MACRS and available bonus depreciation for tax

- Implement production monitoring to validate useful life

| Year | Book Value (Beginning) | DDB Rate (25%) | Depreciation Expense | Book Value (Ending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | $750,000 | 25% | $187,500 | $562,500 |

| Year 2 | $562,500 | 25% | $140,625 | $421,875 |

| Year 3 | $421,875 | 25% | $105,469 | $316,406 |

| Year 4 | $316,406 | 25% | $79,102 | $237,304 |

| . | . | . | . | . |

| Year 8 | $66,825 | Switch to SL | $16,825 | $50,000 |

Note: In later years, the company would switch to straight-line depreciation to reach the salvage value exactly at the end of year 8.

Example 2: Commercial Real Estate

A company purchases a commercial office building for $5,200,000, which includes $800,000 for the land. The building has several distinct components with different useful lives:

- Building structure: $3,000,000 (40 years)

- HVAC system: $600,000 (15 years)

- Roof: $400,000 (20 years)

- Interior fixtures: $400,000 (10 years)

Component Approach Implementation

The company implements component depreciation, treating each major building component as a separate asset with its own depreciation schedule. This approach:

- More accurately reflects the economic consumption of each component

- Simplifies accounting for future replacements (e.g., when the roof is replaced)

- Provides more precise financial reporting

- Requires more detailed record-keeping and tracking

Annual Depreciation Calculation

Using straight-line depreciation for each component:

- Building structure: $3,000,000 ÷ 40 years = $75,000 per year

- HVAC system: $600,000 ÷ 15 years = $40,000 per year

- Roof: $400,000 ÷ 20 years = $20,000 per year

- Interior fixtures: $400,000 ÷ 10 years = $40,000 per year

- Land: Not depreciated

Total annual depreciation: $175,000

Example 3: Technology Assets

A financial services company purchases 200 high-end workstations for its trading floor at $3,000 each ($600,000 total). The company expects the workstations to have a useful life of 3 years with no salvage value, but anticipates they will become technologically obsolete quickly.

- Rapid technological obsolescence

- High volume of identical assets

- Potential for early replacement

- Data security concerns at disposal

- Use sum-of-years-digits method

- Implement group asset accounting

- Consider Section 179 deduction for tax

- Establish secure data destruction protocol

Chart: Sum-of-years-digits depreciation for technology assets over 3 years

Sum-of-Years-Digits Calculation

For the workstations with a 3-year useful life:

- Calculate sum of years: 3 + 2 + 1 = 6

- Year 1 fraction: 3/6 = 1/2

- Year 2 fraction: 2/6 = 1/3

- Year 3 fraction: 1/6

Year 1 depreciation: $600,000 × (3/6) = $300,000

Year 2 depreciation: $600,000 × (2/6) = $200,000

Year 3 depreciation: $600,000 × (1/6) = $100,000

Example 4: Vehicle Fleet

A delivery company maintains a fleet of 50 delivery vans purchased for $40,000 each ($2,000,000 total). The vans are expected to be driven approximately 200,000 miles over a 5-year period before being sold for an estimated $5,000 each.

Units of Production Method

Since the vans’ value diminishes based on usage rather than time, the company uses the units of production method:

- Depreciable cost per van: $40,000 – $5,000 = $35,000

- Depreciation per mile: $35,000 ÷ 200,000 miles = $0.175 per mile

| Year | Miles Driven | Depreciation Calculation | Annual Depreciation | Accumulated Depreciation | Book Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | 50,000 miles | 50,000 × $0.175 | $8,750 | $8,750 | $31,250 |

| Year 2 | 45,000 miles | 45,000 × $0.175 | $7,875 | $16,625 | $23,375 |

| Year 3 | 40,000 miles | 40,000 × $0.175 | $7,000 | $23,625 | $16,375 |

| Year 4 | 35,000 miles | 35,000 × $0.175 | $6,125 | $29,750 | $10,250 |

| Year 5 | 30,000 miles | 30,000 × $0.175 | $5,250 | $35,000 | $5,000 |

This method ties depreciation directly to asset usage, providing a more accurate reflection of how the vehicles lose value. The company tracks mileage through fleet management software that integrates with the accounting system, ensuring accurate and timely depreciation calculations.

These practical examples illustrate how depreciation principles apply to different asset types and business scenarios. By selecting appropriate methods and implementing best practices tailored to each asset class, organizations can ensure their depreciation practices accurately reflect economic reality while maintaining regulatory compliance.

Conclusion

Mastering fixed asset depreciation is essential for financial accuracy and sound business decision-making. Throughout this article, we’ve explored the various dimensions of depreciation management, from method selection to regulatory compliance, best practices, and practical applications.

Key Takeaways

Strategic Method Selection

Choose depreciation methods that align with how assets lose value in your business, balancing financial reporting objectives with tax considerations.

Robust Documentation

Maintain comprehensive asset records, document key decisions and estimates, and implement strong controls to ensure accuracy and auditability.

Regular Review

Periodically reassess depreciation assumptions, conduct impairment testing, and adjust estimates to reflect changing business conditions and asset utilization.

Compliance Focus

Stay current with evolving accounting standards and tax regulations, implementing processes to ensure ongoing compliance and proper disclosure.

Effective depreciation management goes beyond technical accounting—it provides valuable insights into asset performance, informs capital investment decisions, and contributes to accurate financial reporting that stakeholders can rely on.

By implementing the strategies and best practices outlined in this article, your organization can transform depreciation from a routine accounting exercise into a valuable financial management tool that enhances decision-making and supports long-term business success.

Remember that depreciation practices should evolve as your business changes and as regulatory requirements shift. Regular review and refinement of your approach will ensure your depreciation methodology continues to provide an accurate picture of your organization’s fixed asset economics.

About the Author

Tiago Jeveaux

Tiago Jeveaux is the Chief Operating Officer at CPCON Group with vast experience helping organizations optimize their asset management practices. He has led digital transformation initiatives across manufacturing, healthcare, energy, and transportation sectors, focusing on the integration of emerging technologies with financial and operational processes.

Related Articles

5 Ways to Prepare for Your Next Fixed Asset Audit

May 9, 2025 • 7 min read

5 Common Asset Tracking Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

April 15, 2025 • 6 min read

https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/accounting/capital-expenditure-capex/https://cpcongroup.com/insights/mastering-fixed-asset-depreciation-for-financial-accuracy/