FAQ: How Should Financing Affect Capital Budgeting Decisions?

Family business directors must properly distinguish between capital structure and capital budgeting decisions to make the best decisions. In this week’s post, we answer a frequently asked question that leads us into a discussion of what is known as the “separation principle.” In short, what are the relevant cash flows for capital budgeting analysis? And, when is it appropriate to combine investing and financing decisions? If you have ever struggled with these questions, this week’s post has the answers you need.

Q: Should we deduct interest expense when calculating the IRR on a project?

A: No. For most capital budgeting applications, interest expense should not be deducted from forecast cash flows when calculating IRR. When the hurdle rate reflects the weighted average cost of capital, the relevant measure of return should reflect cash flows available to both debt and equity holders (i.e., before deducting interest expense).

As a general rule, family business directors should strive to keep investing decisions separate from financing decisions. There are two primary rationales for this “separation principle”:

- The operating managers responsible for selecting and executing capital projects generally have no control over the family business’s financing decisions. Considering potential capital projects on a debt-free basis aligns the analysis with the perspective of the responsible manager. The specific financing used to fund a given capital project is rarely the responsibility of an operating manger, but is ultimately the decision of corporate directors.

- The actual funding sources used to finance the specific project are not relevant to the decision to accept or reject the project. At first blush, this is counter-intuitive – surely the funding sources actually used are what matter the most. The flaw with this reasoning is that family business capital structures can generally be modified independently of investment activity. Let’s consider a simple example to illustrate. Assume a family business has a target capital structure of 75% equity and 25% debt. Following a couple very profitable years, the company’s actual capital structure has drifted to approximately 80% equity and 20% debt. As a convenient means of moving back toward the target, the company plans to finance 100% of a proposed $5 million capital project. What is the appropriate hurdle return for this project? The appropriate hurdle return is the weighted average cost of capital (75% equity / 25% debt) despite the fact that the actual financing will rely on 100% debt. Failing to do so would inadvertently give this project credit for the fact that the company was under-leveraged at the time the project happened to be under consideration. Undertaking this capital project is not the only means by which the company can re-lever its capital structure. Through a refinancing transaction, the company can “fix” its capital structure problem without engaging in any capital investment.

Are there any exceptions to the separation principle? Yes, a couple. First, occasionally projects include access to financing not otherwise available to the family business. For example, if a proposed project would be eligible for uniquely advantageous bond financing through a municipality, it may be appropriate to evaluate that project on an equity basis. Second, real estate investments are often evaluated net of the leverage that will be used to finance the project. For many real estate investors, individual projects stand or fall on their own, in contrast to family businesses for which capital projects form an integrated portfolio of activities which are financed as a whole. Furthermore, since many real estate investors are tax pass-through entities, it is customary to calculate returns on real estate on a pre-tax basis.

Whether calculating the internal rate of return on a total capital or equity-only basis, it is essential to ensure consistency among the project cost, the relevant cash flows, and hurdle rates, as summarized in the following table.

The following simple example illustrates proper alignment between the components of the internal rate of return analysis described in the preceding table.

From a total capital perspective (the traditional and preferred viewpoint for capital budgeting), the total investment is the relevant cash outflow against which returns are measured. The aggregate (pre-interest and debt service) cash flows result in a 12.4% internal rate of return. From a financial point of view, the project is acceptable if the weighted average cost of capital for the family business is less than 12.4%.

From an equity perspective (appropriate for the exceptional cases noted above), the relevant cash outflow is only the equity contributed by the family business to the project. Annual project cash flows are reduced by both principal and (after-tax) interest payments on the assumed debt, yielding an internal rate of return of 17.6%. While this IRR is higher than that under a total capital approach, the relevant hurdle rate for evaluating the acceptability of the project is the family business’s cost of equity (which will exceed the weighted average cost of capital).

Why Does This Matter?

Family business directors face three principal inter-related strategic financial questions:

- Capital Structure: How should is the appropriate mix of debt and equity financing for our family business?

- Capital Budgeting: What are the optimal reinvestment decisions for our family business?

- Dividend Policy: What form should returns to our family shareholders take?

As depicted in the preceding chart, the answers to each of these three questions have consequences for the others, and family business directors should strive to answer these questions on an integrated, rather than piecemeal, basis.

Mercer Capital’s Family Business Director Blog provides corporate finance and planning insights to multi-generational family business directors.

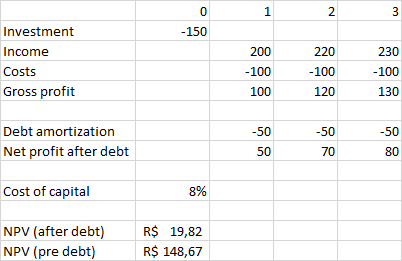

Why do not include loan payments in NPV?

Textbooks in finance claim that one should not include financial cashflows in capital budgeting. I get the idea of not including interest (as it should be included in the cost of capital), but I don’t understand why debt repayments theoretically would not affect NPV. Suppose an initial investment of -150, totally funded by debt. Income for years 1,2 and 3 are 200, 220 and 230. Costs are set to -100 for three years so gross profits are 100, 120 and 130. Assume no NOWC and no taxes. With a cost of capital of 8%, the NPV would be 148,67. Now suppose debt installments of -50 during the three-year period so all debt is paid at the end of the project. Net profits for years 1,2 and 3 are 50, 70 and 80, yielding an NPV of 19,82. Maybe one could think that 19,82 is the NPV for the investor. Is that right? What am I missing out here? Is is because the NPV of a loan is zero? Suppose a delayed payment. In my mind, that would affect the NPV of the project. Finance textbooks usually consider no repayment, although real projects usually do consider.

asked Sep 17, 2019 at 14:58

33 1 1 gold badge 1 1 silver badge 4 4 bronze badges

$begingroup$ In a large company a single person will not be involved in both financing the company and choosing/implementing projects. In Corporate Finance books it is assumed that the people responsible for financing will estimate a WACC cost of capital at which the company can be financed and give this to people responsible for evaluating projects. The people evaluating projects are thus relieved from knowing the details of stock issuance, loans, loan repayments, etc. The just assume a WACC and look only at the Operating Cash Flows for the project. This is by assumption. $endgroup$

Commented Sep 17, 2019 at 15:54

$begingroup$ Thanks @AlexC. But what about real-life problems? I understand that we want to know if a project is valuable independent from its financing. However, wouldn’t financing affect whether the project really adds value to the company? $endgroup$

Commented Sep 17, 2019 at 16:24

3 Answers 3

$begingroup$

I think the fundamental misunderstanding you have is that you think that Cash Flows from Financing Activities includes interest payments. It does not. In only includes principal repayments. Cash Flows from Operating Activities does include interest payments. Look at any Income Statement + Cash Flow Statement on any 10-K from sec.gov and you’ll see this to be true.

As Charlie Munger says, “I’ve never heard an intelligent cost of capital discussion”.

Cost of capital can mean two things, and it’s often not clear which definition people are using. Cost of capital can mean:

- how much it costs you to borrow money (e.g. 8% annualized interest rate to borrow $1m with 10% outstanding principal repayment every year)

- the opportunity cost of deploying your capital into whatever you’re calculating NPV for (e.g. 9% historical nominal return from the S&P 500)

The discount rate matters for the second. It doesn’t matter for the first.

Now, all that being said, to calculate the NPV of an investment, all that matters is how much cash you outlay initially and how much you’re getting back at each period of time. Therefore, you are correct that debt repayment, in terms of both interest and principal should be taken into account when calculating NPV.

Let’s take two examples. Let’s say you’re thinking about buying a private business for $1m dollars that has $1m book value (assets – liabilities, or in other words, equity) and returns 10% free cash flow every year for five years after which we liquidate the business and sell the $1m of assets net of liabilities. For sake of example, the only other investment possibility you have is to invest in the S&P 500, which will return you 9% guaranteed (again, for sake of example). Because this 9% is your opportunity cost, it will be used as the discount factor.

We’ll first do the calculations using $1m equity (money you own), then we’ll do it with a mix of equity and debt with a specific cost of capital, where the cost of capital definition is the first one from above.

Example 1 (Use $1m equity to buy business):

$text = \$100,000 / 1.09 + \$100,000 / 1.09 ^ 2 + . + \$100,000 / 1.09 ^ 5 + \$1,000,000 / 1.09 ^ 5 – \$1,000,000$

Example 2 (Use $500k equity to buy business and $500k debt at 5%):

The interest payments are as follows, which I plugged into: https://www.creditkarma.com/calculators/amortization/

Year 1: $22,950 Year 2: $18,331 Year 3: $13,476 Year 4: $8,372 Year 5: $3,008

Cumulative principal you’ve paid off every year is: Year 1: $90,278 Year 2: $185,174 Year 3: $284,926 Year 4: $389,780 Year 5: $500,000

$text = (\$100,000 – \$22,958 – \$90,278) / 1.09 + (\$100,000 – \$12,331 – \$94,896) / 1.09^2 + (\$100,000 – \$3,008 – \$99,752)/ 1.09^3 + (\$100,000 – \$13,476 – \$$ 104,854)/ 1.09^4 + ($100,000 – $8,372 – $110,220)/ 1.09^5 + $1,000,000/ 1.09^5 – $500,000

Notice that the cost of debt here has nothing to do with the discount factor. The opportunity cost of capital has everything to do with it. The cost of capital (first definition) is handled by the interest and principal payments on the numerator. Also notice that the NPV of the second calculation is bigger because your return on equity was higher (you only put up $500,000 instead of $1m and you were able to borrow at 5% while getting a 10% return on the money, thus covering your cost of capital (first definition)).

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/faq-how-should-financing-affect-capital-budgeting-decisions-harmshttps://quant.stackexchange.com/questions/48728/why-do-not-include-loan-payments-in-npv